Reading Greek in Ammianus Marcellinus' history. Prophecies, proverbs and vocabulary...

The instances where Ammianus uses the greek language are including proverbs, verses, inscriptions, and sometimes just vocabulary, either cause the historian just preferred it or cause he wanted to give some etymological explanation.

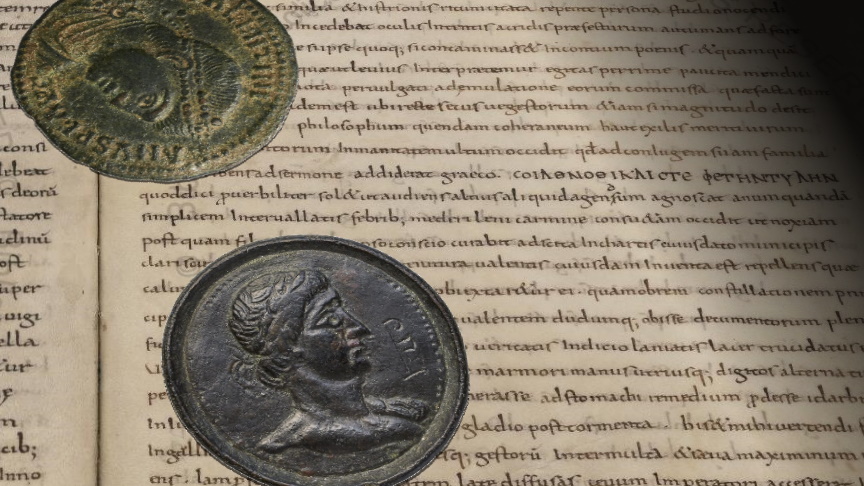

The oldest manuscripts containing Ammianus' history are two and both are coming from the 9th century CE. Unfortunately only one of these is usable. The rest are since 14th-15th c. CE.

- V: Codex Fuldensis, 9th c. CE , Vat. Lat. 1873. Its greek script is usually in capitals, while sometimes seems misspelled or incomplete. It covers the whole surviving work [books 14-31] and it can be seen digitalized in https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.1873.

- M: fragmenta Marburgensis [Codex Hersfeldensis], 1st half of 9th c. CE, Kassel 2° Ms. philol. 27. Mostly lost; only 6 leaves have survived, which can be seen digitalized in https://orka.bibliothek.uni-kassel.de/viewer/image/1336391032501/

- G: Happily Sigismund Gelenius had transcribed the aforementioned, now lost, manuscript, which was printed in 1533; as its preface can tell [cf. Seyfarth, 1978a, p. viii, xii]. Gelenius uses lower case letters for the greek writing. This transcription is included in a work under the title 'Omnia quam antehac emendatiora' of 1533, pp. 545–786, and ends in the 30th book.

For this compilation great help was the original text as given by Rolfe since 1935, cause he preferred the greek writing where suitable. But of course the critical edition by Seyfarth of 1978, too. The texts were compared with the V manuscript and the G transcription by Gelenius of the M manuscript. Generally Gelenius' transcription [in lower case] is correct, i.e. corresponds to right spelling and writings. I don't know if this is what he saw, or corrected it by his own knowledge. V manuscript [in upper case] seems misspelled; sometimes the transcriber had substituted eg. H with N or K, or Ε with Θ, or Α with Δ or Λ, as similarly written, while it's obvious that he couldn't understand occasionally that two drawn lines would form a greek letter, and he copied them as two different resembling letters. The obvious conclusion is that the transcriber wasn't familiar with greek and tried to copy visually what he was seeing.

- Proverbs & Verses

- 01. Hypsenor's death by Homer: Res Gestae 15.8.17

- 02. Menander's demon: Res Gestae 21.14.4

- 03. Galactophagi & Abii: Res Gestae 23.6.62

- 04. The oxen of Ceasar Marcus: Res Gestae 25.4.17

- 05. The celebration: Res Gestae 29.2.25

- Prophecies?

- 06. Constantius' II death: Res Gestae 21.2.2

- 07. Valens' death: Res Gestae 29.1.33

- 08. Before the war against Goths: Res Gestae 31.1.5

- Vocabulary

- A greek translation of the hieroglyphs of an Egyptian inscription

- 09. The obelisk from Heliopolis: Res Gestae 17.4.17-23

- References

Proverbs & Verses up

01. Hypsenor's death by Homer: Res Gestae 15.8.17 up

Ammianus places Julian, right after he was proclaimed Caesar in November 356 CE, being led towards the imperial palace, while whisperring the following verses:

| ἔλλαβε πορφύρεος θάνατος καὶ μοῖρα κραταιή | Dark-red death and mighty destiny caught [him] |

It's from Homer's Iliad [5.73] describing how Hypsenor, a Trojan priest, was killed by Eurypylus, one of the Achaeans. I'm not sure if Ammianus wanted to create some tragic irony, implying Julian's violent death that would occur years later.

|

| fig.01: from Vat. Lat. 1873, 23v: ΕΛΛΑΒΕ ΙΤΟΡΦΥΡΕΟC ΘΑΝΑΤΟC ΙCΑΤ ΜΥΡΑΤΕΗ. It seems misspelled. G is correct [1533, p. 574] |

02. Menander's demon: Res Gestae 21.14.4 up

Speaking about Constantius II in 361 CE ca, Ammianus is placing him confessing to his closest, that some vague apparition occasionally was appearing to him, which then had disappeared [21.14.2]. And on this the historian is giving a parallelism with some verses of comic poet Menander.

|

ἅπαντι δαίμων ἀνδρὶ συμπαρίσταται εὐθὺς γενομένῳ, μυσταγωγὸς τοῦ βίου. |

a demon is standing next to each man, since right after being born, as a guide of life |

I don't know if it matters, but Menander was a comic poet.

|

| fig.02: from Vat. Lat. 1873, 86v: ΑΠΑΝΤ ΔωΜωΝ ΛΝΔΡΙ CΤΛΤΛΙ ΕΥΟΥΕ ΓΕΝΟΛΙΕΝω ΛΙΥCΤΛΤωΓΟC ΤΟΥ ΒΙΟΥ |

Regarding the writing: in V manuscript it seems a little unclear. If I could say something, this would be that the transcriber possibly saw or understood '-σταται' instead of 'συμπαρίσταται'. Gelenius' transcription [1533, p. 657] is totally clear but slightly different, though without some alternate approach "ἅπαντι δαίμων ἀνδρὶ τῷ γενομένῳ, ἅπαντος ἐστί μυσταγωγὸς τοῦ βίου".

Happily the verses can be confirmed by Plutarch [De Tranq. 474b]; where just a letter is different without changing the meaning. While Plutarch was also adding in the end of the 2nd line the word 'ἀγαθός', giving the meaning that the demon was a 'good guide' not just guide. Maybe Ammianus omitted it cause he was referring to Constantius II.

03. Galactophagi & Abii: Res Gestae 23.6.62 up

Ammianus, while narrating the story and deeds of Julian, is giving some short information about the people who lived around the lands of the Scythians in Asia. Among them, he wrote, were some tribes mild and pious ['mites et pios'], like Iaxartae and Galactophagi, and he quotes a line frome Homer [Il. 13.6]:

| γαλακτοφάγων Ἀβίων τε δικαιοτάτων ἀνθρώπων | and of galactophagi [=milk-eaters] [and] Abii [=nomads or peaceful], most righteous men |

Looking at Homer's passage there's no total certainty what is a proper name and what is an adjective-attribute. Homer in those lines is giving surely the names of Thracians and Mysians and many other epithets, of which it's not clear what is what. Galactophagi literally means milk eaters, and it's a totally clear etymology; while Abii could mean nomads [from 'without living/wealth'] or peaceful [from 'without violence'], or even something else. As I see it Abii it should be a proper name of a tribe in Homer, who surely should be considered attached to the epithet 'most righteous men', while it isn't clear if these were the 'milk-eaters' or some other tribe, or both.

Abii are mentioned by Strabo of the 1st c. BCE [Strab. 7.3.2-9], who reproduces information by previous historians. Like Ephorus of the 4th c. BCE who wrote that there was a Scythian nomad tribe who was fed by horse's milk and was distinguished in justice. But also like Posidonius of the 1st c. BCE, who seems considering all these Homeric epithets attached to Mysians [and specifically to the Mysians of Europe], including the 'abii' as an epithet that was explained as 'without women/family'. Strabo seems to be more of the Posidonius' opinion. Later Arrian of the 2nd c. CE, also uses the term 'abii' [Arr. An. 4.1.1], either as an epithet of Scythians, or a Scythian sub-tribe. In all these works the attribute of the righteous tribe isn't missing.

|

| fig.03: from Vat. Lat. 1873, 113r: ΓααΚΤΟΦΑΤΩΝ ΑΒΙωΝ ΤU ΔΑΚΑΙΟΤΑΤωΝ αΝΘΡωΠωΝ. Slight mistakes. Gelenius [1533, p. 689] is correct. |

04. The oxen of Ceasar Marcus: Res Gestae 25.4.17 up

Ammianus trying to give a total picture of emperor Julian, writes that he had become more superstitious rather than religious, resembling with the previous emperor Hadrian. Julian seemed sacrificing many animals and on this Ammianus quoted a saying meant for previous emperor Marcus [Aurelius].

|

οἱ βόες οἱ λευκοὶ μάρκῳ τῷ καίσαρι χαίρειν. ἄν πάλι νικήσῃς, ἄμμες ἀπωλόμεθα. |

the white oxen salute Caesar Marcus. if you win again, we indeed will die. |

|

| fig.04: from Vat. Lat. 1873, 113r: ΟΙ ΛΕΥΚΟΙ ΒΟΕC ΜΑΡΚω Τω ΚΑΙΡΙΝ ΑΝ ΠΛΛ ΝΙΚΗCΗ ΗΜΕΙC ΑΠωΛΟΜΕΘΑ. Slight mistakes. Gelenius [1533, p. 709] seems spelling correctly. |

05. The celebration: Res Gestae 29.2.25 up

For the years of about 371 CE, when Valens had started a persecution against pagans, Ammianus is describing the case of a certain philosopher called Coeranius. He was executed after resisting to tortures. The reason was a letter to his wife [coniugem], where the following phrase was included:

| σὺ δὲ νόει καὶ στέφε τὴν πύλην | and you, do understand and crown the gate [with a wreath] |

Crowning the gate is probably an action of celebration [check example in den Boeft et al., 29.2013, p. 112]. The proverb is giving a first impression of urging to think/understand & celebrate. Ammianus explains the phrase in latin: "which [one/he] is accustomed to say [it] proverbially, so that the hearer realizes something higher/deeper [=important] to be done" [=quod dici proverbialiter solet, ut audiens altius aliquid agendum agnoscat].

I have a doubt about the translation of the word 'agendum' [= to be done]. It seems to be a gerundive of the verb 'ago' with the form of future passive participle, and as such it could have been translated with two ways; here giving a different meaning. Gerundive express something 'to be done'; i.e. that is about to come, that is ready to be done. However, really often it gives a meaning of necessity, obligation; i.e. something that 'should be done' [: totally equivalent with the greek verbal adjectives ending to -τεος] [among others, Palmer, 1954, p. 321]. So here, according to Ammianus' explanation, this proverb could have the meaning that something important is about to occur [so 'do prepare'], or that something important should be done [as urging the wife to do something]. Unclear for me. But in both cases it may have irritated a christian emperor of the time, as it declares a celebration by a pagan.

Prophecies? up

In den Boeft et al. [31.2018, p. 253ff] the following three passages [06, 07 & 08], written in greek, are connected as prophesying future deaths & disasters; quite expected and rational. Continuing the authors are naming them as 'vaticinia ex eventu' [=prediction from the event]; i.e. as foretelling phrases composed by the historian after the events. I can't feel totally sure about this, even if it looks like. In the 1st example [21.2.2, under 06], we could have such a case but it's unclear if this was composed by Ammianus and further if Ammianus was convinced about it. In the rest two [29.1.33, under 07 & 31.1.5, under 08] Ammianus either is reproducing explicitly rumors of fulfillment or giving alternative explanations, respectively. And generally though he had declared his belief in divination, he had underlined that it was a matter of human interpretation of the signs, that could be wrong. Maybe Ammianus used indeed these 'omens' theatrically for some tragic irony, but without being possible to see if they were his invention or were truly heard.

06. Constantius' II death: Res Gestae 21.2.2 up

Sometime in 360 CE ca, Julian was in Vienne of Gaul; shortly before emperor Constantius II would die and Julian would dominate over the whole Roman empire. There Ammianus narrates that one night Julian saw in his dream an apparition [imago] repeating to him the following verses:

|

ζεὺς ὅταν εἰς πλατὺ τέρμα μόλῃ κλυτοῦ ὑδροχόοιο, παρθενικῆς δὲ κρόνος μοίρῃ βαίνῃ ἐπὶ πέμπτῃ εἰκοστῇ, βασιλεὺς κωνστάντιος ᾿ασίδος αἴης τέρμα φίλου βιοτοῦ στυγερὸν καὶ ἐπώδυνον ἕξει. |

When Zeus reaches the wide bound of glorious Aquarius, and Saturn steps on the 25th degree of Virgo, emperor Constantius of Asian land, will have an abominable and painful end of beloved life |

a. Ammianus calls these lyrics heroic [heroes], possibly referring to their meter. Probably the verses are appeared as prophetic for Constantius' death later in late 361 CE; who however according to Ammianus died by some fever [febris, 21.15.2]. Few lines earlier [21.1] Ammianus makes clear that he believes in fate and divination, that could include dreams. And Julian [21.1.6] seemed that in Ammianus' eyes was capable for such prophetic activities [: quae callebat]. And of course it should be noted Ammianus' somehow preference for pagan Julian. Nevertheless, repeating some Cicero's quote [Cic. N.D. 2.12], he underines that the gods' signs could be misleading cause of human interpretation [conjectura: 21.1.14]. And regarding Ammianus' thoughts, we should maybe remember his review on Julian when speaking about his defects [vitia / 25.4.16ff: that was seen under 04]. He was thinking of the pagan emperor as "surrendered to inquiry of presentiments/ omens too much" [praesagiorum sciscitationi nimium deditus], while he called him superstitious rather than religious.

However a problem here is that this sign-dream was only witnessed by Julian. And it's noteworthy that Ammianus also adds Julian's desire to attack Constantius [21.1.6: cupiditatem... incessere ultro Constantium], seemingly as a result of the signs that he had seen about Constantius' forthcoming death. One can't ignore here the possibility of an implied psychological factor; or more cynically of a temporary plan for attack, as Julian has been already hailed as Augustus by his troops in 360 CE [20.4.14]. Maybe it's not coincidence that the historian doesn't come back to these lyrics when speaking about Constantius' death [21.15.2]; a pattern that he's using elsewhere, but mainly to give later rumors of fulfillment, as we'll see [under 07].

And generally it's a little obscure how these verses came to light in the end. Did Julian shared them? When Ammianus will talk about relevant signs seen by Constantius [under 02], he will place him confessing these stories to his 'closest' [21.14.2: confessus est iunctioribus proximis]. It sounds like a rumor. The incident is set about a year before Constantius' death, i.e. late 360 CE. Ammianus, according to his narrative, seems being a soldier under the command of Ursicinus [eg. 15.5.22]. Now Ursicinus, though had been in Gaul [where was Julian], he probably have been dispatched back to the east since 358 CE ca [18.6], where also Ammianus is implied to take part, as the 1st plural of verbs is used. He seems to be at the east till at least the Siege of Amida in 359. And then his traces are a little unclear. So we can't know if he would have even returned in Gaul and be specifically in Vienne of Gaul at the time, according to his own previously narrated deeds.

I'm not sure if Ammianus here is convinced about this dream and its value.

b. And a thought about the astronomical information using the software Stellarium v. 0.22.2 [https://stellarium.org/]. Though it should be underlined that it's said with some diffidence:

the omen seems unusually precise regarding the positions of the planets. At least with a first look. I've tried to search on this. Neugebauer & Van Hoesen [1964, p. 66-67], discussing on the known debate of the exact date of Constantius' death [: Oct 5 or Nov 3 of 361], are mentioning that the planets' positions of the aforementioned omen/ horoscope can't help; specifically: "unfortunately its data agree sufficiently well with both traditional dates, 361 October 5 and November 3, since only the positions of Saturn and Jupiter are mentioned and the latter is at the given time practically stationary" [also check Jones [1999, p. 346]. In general, planets are seeming moving on the sky's zodiac belt with the same direction, and different velocities. And stationary is an astronomical term usually expressing the start and the end of an apparent retrograde planet's motion; i.e. when changes direction. During this motion the planet will seem in the sky stopping, then going backwards for some time and then again going forward; with result seeming being in some same specific part of the sky for some time. This time could be months.

I couldn't find some records via web for it regarding the specific years and I've tried to confirm it via the known software Stellarium v. 0.22.2 [which, as I've read, is using the VSOP87 model, being accurate for 1'' over 2.000 years for these planets; 1'' = 1/3600 of a degree]. According to it, it was true; and not only for Jupiter, which in any case its position was vague, but for Saturn, too. In the end both planets could be seen in these constellations [Virgo for Saturn, Aquarius for Jupiter] & positions for some months, going back and forth. And in fact for the biggest part of 361 CE; i.e. a period from about the assumed date of the omen, start of 361, till the death of Constantius on Nov 3, 361.

If the info from Stellarium v. 0.22.2 are accurate, there's a period of at least 10 months, where the astronomical data seem that could meet the criteria; a period that came after the verses/ omen. In this period Julian could just attack to Constantius II, if the war between them was inevitable and there was a plan, and so a death could occur. I can't know if this vagueness of the verses was on purpose and by whom. But my feeling says that, whoever invented it, Ammianus was aware of this length of time; in the 'vocabulary' part of this post we'll see that the historian was familiar with relevant astronomical terms of the time.

In any case, a little later pagan historian Zosimus of the 5th c. CE [NH 3, 9] repeats the incident and the verses. According to him, these were told by Helios [sun] to Julian in a dream, when Julian was unwilling to conduct a civil war against Constantius II.

07. Valens' death: Res Gestae 29.1.33 up

In 371 CE ca Valens, under the fear of conspiracy, started a mass pagan persecution; as described by Ammianus in his 29th book. The historian is giving the quick impression that he was an eyewitness of some events in Antioch, using the phrase 'what we can recall' [quae recolere possumus: 29.1.24]. While he seems to excuse somehow Valens for his cruel actions, calling him 'somehow foolish' [subrusticus] and describing recent plots against him that probably would have caused some fear.

In any case, the Roman authorities after some search, reached to two certain pagan philosophers, Patricius and Hilarius. They were accused that with the help of divination have found out the name of the Valens' successor. Their method included a tripod, a hanging ring and letters, like a fortunetelling pendulum. After some torture, they were asked by the judges ironically if they have foreseen their suffering. And they answered with some greek lyrics ending into the following three, underlining their no-repentance.

|

οὐ μὰν νηποινί γε σὸν ἔσσεται αἷμα καὶ αὐτοῖς τισιφόνη βαρύμηνις ἐφοπλίσσει κακὸν οἶτον ἐν πεδίοισι μίμαντος ἀγαιομένοιο ἄρηος. |

and your blood truly won't be unavenged and Tissiphone most wrathful will arm with evil doom against them, when Ares will show indignation in the plains of Mimas |

The verses are called familiar by Ammianus ['notissimos'/ very well known]. It's unclear if this means that he heard them then or that were generally known verses. But it's also noteworthy the mention of the plains of Mimas. Mimas was a region [possibly containing a mountain] in Asia minor, mentioned already since Homer [Od. 3.141] as opposite to island Chios. Further pagan historian Zosimus of the 5th c. [NH 4.15] is also describing the incident of mass pagan persecution [without the curse/ verses], specifying the victims as Hilarius of Phrygia and Patricius the Lydian. Territories of Asia minor, somehow next to the aforementioned Mimas; thus maybe there was some background/ influence around the origin of these words.

The 3rd line of this curse [-oracle] is repeated by Ammianus, when finishing with Valen's deeds [31.14.8]. He's actually writing there about Valens' increasing fear [timidus] through the years, cause of the troubles of his life. Fact that made him tremble/ shudder [horrebat] at the hearing of the name Asia, cause as he had heard there was a mountain Mimas near the city of Erythrae in Asia minor. And this made me wonder what Ammianus was trying to imply.

Continuing he adds an anecdote, probably unconfirmed as he writes "it is said" [dicitur], that in the battlefied of Adrianople, where Valens was lost in 378 CE, was later found a tomb with some Mimas being buried there. Probably Ammianus is giving just a rumor for the fulfillment of the prophecy, but totally unconfirmed even by him. While according to what he had narrated, Valens lost not by some Greek pagans, but by Goths. Centuries later, the Byzantine historians Cedrenus [PG 121, 597] & Zonaras [13.16, PG 134, 1165], described this fulfillment, with more details but with an almost totally different story. Regarding the fact of the mass pagan persecution there's also an allusion in an homilia by John Chrysostom of 386 CE ca [check Harkins, 1984, p. 112 & den Boeft et al., 29.2013, p. 72].

The greek text of this excerpt should be considered of the most difficult...

|

| fig.08: from Vat. Lat. 1873, 177r, misspelled: ΟΥ ΜΛΝ ΝΗΠΟΙΝΙ ΓΕΓΟΝ ΕCCΕΤΑΙ ΑΛΜ ΚΑΙ ΑΥΤΟΙC ΤΙCΙΦωΝΗ ΒΑΡΥΜΗΝΙC ΕΦΟΠaΗCΕΙ ΚΑΚΟΝ ΟΙΤΟΝ ΕΝ ΠΕaΙΟΙCΙ ΜΜΑΝΤΟC ΑΙΑΕΟΜΕΝΟ ΚΑΡ |

In the V manuscript one maybe could recognize most of the words; but there would be surely a problem with 'blood/αἷμα' and the finish of the 3rd line, as totally incomprehensible. And Gelenius [1533, p. 761], though he had confirmed the word 'blood', doesn't actually help with the rest here. It was later in 1868 when Haupt gave the solution, comparing the excerpt of 21.1.33 [fig.08] with its repetition in 31.14.8 [fig. 09].

|

| fig.09: from Vat. Lat. 1873, 205r-v: ΕΝ ΠΑΙΔΙΟΙCΙ ΜΙMΛΝΤΟC aΙaΛΙΛaIOΜENOIO AΡ |

08. Before the war against Goths: Res Gestae 31.1.5 up

It's not clear if the following incident was a rumor or Ammianus had a direct knowledge. In any case he's writing that in 375 CE ca, when some walls in Constantinople were torn down [Chalcedon], so that some baths to be built, the following hidden inscription was revealed:

|

ἀλλά ὁπόταν νύμφαι δροσεραὶ κατὰ ἄστυ χορείῃ τερπόμεναι στρωφῶνται ἐυστεφέας κατ᾽ ἀγυιάς, καὶ τεῖχος λουτροῖο πολύστονον ἔσσεται ἄλκαρ, δὴ τότε μυρία φῦλα πολυσπερέων ἀνθρώπων ἴστρου καλλιρόοιο πόρον περάοντα σὺν αἰχμῇ, καὶ σκυθικὴν ὀλέσει χώρην καὶ μυσίδα γαῖαν, παιονίης δ᾽ ἐπιβάντα σὺν ἐλπίσι μαινομένῃσιν αὐτοῦ καὶ βιότοιο τέλος καὶ δῆρις ἐφέξει. |

but when fresh brides, delighted with a city dance, will whirl crowned in the streets, and a grievous wall will be the defence of a bath, then countless races of wide-spread men, passing across the way of flowing Ister [Danube] with spear, will destroy the Scythian land and the Mysian country, and when they walk upon Paionia with raging hope, life's end and battle will prevail there |

This has been interpreted as prophesying the following Gothic war. Before these verses Ammianus speaks vaguely about the forth-coming [futura]. But, just right after these lines, he writes: "Nevertheless we have learned this reason, around the seed of all destruction and the origin of the various disasters, that the madness of Mars caused by confusing everything with unusual fire" [31.2.1: Totius autem sementem exitii et cladum originem diversarum, quas Martius furor incendio insolito miscendo cuncta concivit, hanc comperimus causam].

And he's giving for many paragraphs historic and ethnographic information, starting with how Goths and Alans were pushed by the Huns. By this 'nevertheless' [autem] he's obviously declaring some opposition to the previous inscription-prophecy, at least regarding explanation. He seems clearly preferring more rational interpretations; at least for this incident.

In any case these verses have been reproduced [slightly enriched] by christian Socrates of the 5th c. C [HE IV, 8].

Vocabulary up

In his history Ammianus, though wrote it in latin, many times he's using greek words; so to explain terms, give some etymology, or other times just by his preference. Generally as a part of vocabulary. Most times these terms, though they are greek, they are written with the latin alphabet. And they were usually followed by an expression like: 'as we call it', or 'as Greeks call it', or something similar.

| Res Gestae | word | V manuscript | Gelenius |

| 14.9.7 | greek 'διάκονος': deacon ['servant'], rank in christian church | diaconus [11v] | diaconus [p. 559] |

| 14.11.18 | greek 'φαντασία': appearance [/imaginary], here connected with sleep and dreams | fantasias [14r] | phantasias [p. 562] |

| 16.5.5 | greek 'σισύρα': goat's-hair cloak | syra [28v] | ξυσίρα [p. 581] |

| 17.4.14 | greek 'χαμουλκός': pulling machine | chamulcis [41r] | chamulcis [p. 597] |

| 17.7.11 | greek 'σῦριγξ': many things, here small subterranean recess/ passage of the earth | syringas [44r] | syringas [p. 600] |

| 17.7.13 | greek 'βρασματίας': a kind of earthquake, from greek word for 'boil' signifying an up-down movement | brasmatiae [44r] | brasmatiae [p. 601] |

| 18.6.22 | greek 'ὁρίζων': horizon | oρizontac [55r] | orizontas [p.616] |

| 19.8.11 | greek 'σπαρτός': sown-man. From the myth of Cadmus who sowed the dragon's teeth in the earth, after the advice of Athena, and men were born [Apollod. 3.4.1] | sparto [63v] | Sparti [p. 626] |

| 20.3.4 | greek: 'ἀναβιβάζοντες καί καταβιβάζοντες ἐκλειπτικοί σύνδεσμοι': ascending and descending ecliptic nodes, astronomical term signifying inter alia the celestial points where eclipses occur | αΝΑΒΙΒΑΖΟΝταc et καΤΑΒΙΒΑΖΟΝΤΑC ΕΚΛΙΠΤΙΚΟYC CΥΝΔΕCMOYC [68v] | ἀναβιβάζοντας & καταβιβάζοντας ἐκλιπτικοὺς συνδέσμους [p. 632] |

| 20.3.9 | greek 'σύνοδος': assembly, meeting, here christian | synodos [68v] | synodos [p. 633] |

| 20.3.10 | greek 'μηνοειδής': crescent-shaped, for the moon, phase | menoid [69r] | Μηνοειδής [p. 633] |

| 20.3.10 | greek 'διχόμηνις': half-moon, phase | dichomenis [69r] | διχοτόμος [p. 633] |

| 20.3.11 | greek 'ἀμφίκυρτος': gibbous moon, phase | amficyrti [69r] | ἀμφικύρτου [p. 633] |

| 20.3.11 | greek 'ἀπόκρουσις': waning of the moon | ACTOKPICIN [69r] | ἀπόκρισιν [p. 633] |

| 21.1.8 | greek 'τεθειμένα': things are set/ fixed, here the ones of fate | tethimena [78v] | tethimena [p. 645] |

| 22.8.33 | greek 'εὔξεινος': hospitable, adjective for the 'Black sea' [euphemism] | euxinos [93v] | Euxinus [p. 666] |

| 22.8.33 | greek 'εὐήθης': good-hearted, adjective for 'silly' [euphemism] | euethen [93v] | Euethen [p. 666] |

| 22.8.33 | greek 'εὐφρόνη': cheerful, adjective for 'night' [euphemism] | eufronen [93v] | Euphronen [p. 666] |

| 22.8.33 | greek 'Εὐμενίδες': gracious, name for the goddesses Furies [euphemism] | eumenidas [93v] | Eumenidas [p. 666] |

| 22.8.41 | greek 'ἀχιλλέως δρόμος': the road of Achilles, Racecourse of Achilles, a strip of land near Crimea, geography | ahillios... dromon [93v] | Achilleos... dromon [p. 667] |

| 22.9.7 | greek 'ἀπό τοῦ πεσεῖν': 'from falling', etymological explanation for the name of the city Pessinus, explaining that it may be derived from when goddess Mother fell upon the city | αΠΟ ΤΟΥ ΠΕCΙΙΝ [95r] | ἀπό τοῦ πεσεῖν [p. 668] |

| 22.15.14 | greek 'ἀμφίβιοι': amphibious [animals] | amfiboe [99v] | amphibia [p. 674] |

| 22.15.29 | greek 'τοῦ πυρός': 'of fire', etymological explanation for the name of the shape of pyramid, as resembling to a flame | tu pyros [100v] | τοῦ πυρός [p. 675] |

| 23.6.20 | greek 'διαβαίνειν': 'passing, walking', etymological explanation for the name of the place Adiabena, not passed | diab(v)enin [110r] | diavenin [p. 686] |

| 25.2.5 | greek 'διᾴσσων': rushing through, for shooting stars, meteors | diaissonta [126r] | diaissonta [p. 706] |

| 26.1.1 | greek 'ἄτομος': uncut, for 'atom', physics | atomos [136r] | atomos [p. 718] |

| 26.1.8 | greek 'ζῳδιακόν': zodiac | zodiacum [136v] | zodiacu [p. 719] |

| 30.4.3 | greek 'πολιτικῆς μορίου εἴδωλον': semblance of a portion of politics, Platonic term, here used by Ammianus to describe some juridical malfunction | ΠΟΛΙΤΙΚΗC ΜΟΡΙΟΥ ΙΔωΔΟΝ [186r] | - |

| 30.4.3 | greek 'κακοτεχνία': malpractice, bad art, Epicurus' term for the aforementioned juridical malfunction | ΚΑΚΟΤΕΧΝΙΑΝ [186r] | - |

| 31.12.8 | greek 'πρεσβύτερος': elder, presbyter, christian priest rank | presbyteri [202r] | - |

A greek translation of the hieroglyphs of an Egyptian inscription up

09. The obelisk from Heliopolis: Res Gestae 17.4.17-23 up

Ammianus describing Rome, he's mentioning an obelisk, brought from the city of Heliopolis in Egypt and set up at the time in the Roman Circus Maximus. And he adds a translation of its hieroglyphs in greek that had been made by some certain Hermapion:

|

ἁρχήν ἀπό του νοτίου διερμηνευμένα ἔχει στίχος πρῶτος τάδε λέγει [18] ἥλιος βασιλεῖ ῥαμέστῃ: δεδώρημαί σοι ἀνὰ πᾶσαν οἰκουμένην μετὰ χαρᾶς βασιλεύειν, ὃν ἥλιος φιλεῖ. - καὶ ἀπόλλων κρατερὸς φιλαλήθης υἱὸς ἥρωνος, θεογέννητος κτίστης τῆς οἰκουμένης, ὃν ἥλιος προέκρινεν, ἄλκιμος ἄρεως βασιλεὺς ῥαμέστης. ᾧ πᾶσα ὑποτέτακται ἡ γῆ μετὰ ἀλκῆς καὶ θάρσους. βασιλεὺς ῥαμέστης ἡλίου παῖς αἰωνόβιος. στίχος δεύτερος [19] ἀπόλλων κρατερός, ὁ ἑστὼς ἐπ̓ ἀληθείας, δεσπότης διαδήματος, τὴν αἴγυπτον δοξάσας κεκτημένος, ὁ ἀγλαοποιήσας ἡλίου πόλιν, καὶ κτίσας τὴν λοιπὴν οἰκουμένην, καὶ πολυτιμήσας τοὺς ἐν ἡλίου πόλει θεοὺς ἀνιδρυμένους, ὃν ἥλιος φιλεῖ. τρίτος στίχος [20] ἀπόλλων κρατερὸς ἡλίου παῖς παμφεγγὴς, ὃν ἥλιος προέκρινεν καὶ ἄρης ἄλκιμος ἐδωρήσατο. οὗ τὰ ἀγαθὰ ἐν παντὶ διαμένει καιρῷ. ὃν ἄμμων ἀγαπᾷ, πληρώσας τὸν νέων τοῦ φοίνικος ἀγαθῶν. ᾧ οἱ θεοὶ ζωῆς χρόνον ἐδωρήσαντο. ἀπόλλων κρατερὸς υἱὸς ἥρωνος βασιλεὺς οἰκουμένης ῥαμέστης, ὃς ἐφύλαξεν αἴγυπτον τοὺς ἀλλοεθνεῖς νικήσας, ὃν ἥλιος φιλεῖ, ᾧ πολὺν χρόνον ζωῆς ἐδωρήσαντο θεοὶ. δεσπότης οἰκουμένης ῥαμέστης αἰωνόβιος. λίβος στίχος δεύτερος [21] ἥλιος θεὸς μέγας δεσπότης οὐρανοῦ. δεδώρημαί σοι βίον ἀπρόσκοπον. ἀπόλλων κρατερὸς κύριος διαδήματος ἀνείκαστος, ὃς τῶν θεῶν ἀνδριάντας ἀνέθηκεν ἐν τῇδε τῇ βασιλείᾳ, δεσπότης αἰγύπτου, καὶ ἐκόσμησεν ἡλίου πόλιν ὁμοίως καὶ αυτὸν ἥλιον δεσπότην οὐρανοῦ. συνετελεύτησεν ἔργον ἀγαθὸν ἡλίου παῖς βασιλεὺς αἰωνόβιος. τρίτος στίχος [22] ἥλιος θεὸς δεσπότης οὐρανοῦ ῥαμέστῃ βασιλεῖ. δεδώρημαι τὸ κράτος καὶ τὴν κατὰ πάντων ἐξουσίαν. ὃν ἀπόλλων φιλαλήθης δεσπότης χρόνων καὶ ἥφαιστος ὁ τῶν θεῶν πατὴρ προέκρινεν διὰ τὸν ἄρεα. βασιλεὺς παγχαρὴς ἡλίου παῖς, καὶ ὑπὸ ἡλίου φιλούμενος. ἀφηλιώτης. πρῶτος στίχος [23] ὁ ἀφ̓ ἡλίου πόλεως μέγας θεὸς ἐνουράνιος ἀπόλλων κρατερός, ἥρωνος υἱὸς, ὃν ἥλιος ἠγάπησεν, ὃν οἱ θεοὶ ἐτιμησαν, ὁ πάσης γῆς βασιλεύων, ὃν ἥλιος προέκρινεν, ὁ ἄλκιμος διὰ τὸν ἄρεα βασιλεύς, ὅν ἄμμων φιλεῖ, καὶ ὁ παμφεγγὴς συγκρίνας αἰώνιον βασιλέα... |

Starting from the south there's the translated, the first line says

these: [18] The Sun to King Ramestes: I have granted to you that you rule with joy over the whole world, whom the Sun loves - and mighty Apollo, lover of truth, son of Heron, god-born creator of the world, whom Sun has chosen, the brave [son] of Mars king Ramestes. To whom the earth has subdued by strength and courage. King Ramestes eternal child of Sun. second line [19] Mighty Apollo, standing on truth, lord of the Diadem, who dignified Egypt by possessing [it], who made famous the city of the Sun [Heliopolis], and created the rest of the world, and variously honored the gods who are set up in the city of the Sun [Heliopolis], whom Sun loves. third line [20] Mighty Apollo, all-shining child of Sun, whom Sun has chosen and brave Ares gifted. whose benefits will last for all time. whom Ammon loves, filling the temple of Phoenix with goods. whom gods granted with [long] time of life Mighty Apollo son of Heron, king of the world Ramestes, who preserved Egypt by prevailing over other nations, whom Sun loves, whom gods granted with long time of life. lord of the world Ramestes immortal west second line [21] Sun great god lord of the sky. I have granted to you life unimaginable. mighty Apollo incomparable master of the Diadem, who erected statues of the gods in this kingdom, lord of Egypt, and he adorned the city of Sun [Heliopolis] just like the Sun himself, the lord of sky. he accomplished good work the son of Sun, king immortal. third line [22] God Sun lord of sky to king Ramestes. I have granted to you the power and the authority over all. whom Apollo, lover of truth, lord of seasons and Hephaestus the father of gods has chosen for Ares. king all-gladdening child of Sun, and loved by Sun east first line [23] The great god of the city of Sun [Heliopolis] heavenly mighty Apollo, son of Heron, whom Sun loved, whom gods honored, the ruler of all the earth, whom Sun has chosen, the brave king for Ares, whom Ammon loves, and the all-shining who compared the eternal king. |

Ammianus chose to give just some excerpts and not the whole Hermapion's translation of the inscription. This obelisk has been identified since many years with the Flaminian obelisk in Rome [check eg. Westerfeld 2019, p. 199, fn. 37].

The greek text doesn't appear in any existing manuscript; only the introductory line can be read and then a gap was left so that probably to be filled later.

|

| fig.11: from Vat. Lat. 1873, 41v |

The whole text was given only in the transcription of Gelenius [1533, p. 598]. And some corrections followed. Here appears as it is in Rolfe [1935, p. 326ff] & Seyfarth [1978a, p. 110-111].

There are direct translations of the hieroglyphs; I've found an old one online in Tomlison [1843, p. 180ff]. There're similarities and differences. Just to note that Apollon is Horus.

References & Bibliography: up

- Barnes, Timothy David [1998], Ammianus Marcellinus and the Representation of Historical Reality, 1998

- den Boeft, J., Drijvers, J.W., den Hengst, D., Teitler, H.C. [29.2013], Philological and Historical Commentary on Ammianus Marcellinus XXIX, 2013

- den Boeft, J., Drijvers, J.W., den Hengst, D., Teitler, H.C. [31.2018], Philological and Historical Commentary on Ammianus Marcellinus XXXI, 2018

- Clark, Charles Upson [1904], The text tradition of Ammianus Marcellinus, 1904

- Gelenius, Sigismund [1533], Ammiani Marcellini Rerum Gestarum Libri XVII [transcription of M manuscript], in Omnia quam antehac emendatiora, 1533, pp. 545–786

- Gronovius, Jacobus [1693], Ammiani Marcellini Rerum Gestarum, 1693

- Haupt [1868], Index Lectionum, 1868

- Harkins, Paul (transl.), Saint John Chrysostom, On the Incomprehensible Nature of God (The Fathers of the Church, Volume 72), 1984

- Jones, Alexander [1999], Astronomical Papyri from Oxyrhynchus: (P. Oxy. 4133-4300a), Volume 1, 1999

- Lenski, Noel, Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century A.D., 2014

- Neugebauer, O., Van Hoesen, H. B. [1964], Astrological Papyri and Ostraca: Bibliographical Notes, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 108, No. 2 (Apr. 15, 1964), pp. 57-72

- Palmer, L. R. [1954], The Latin Language, 1954

- Rolfe, John C. [1935], Ammianus Marcellinus. With An English Translation, vol.1, 1935

- Rolfe, John C. [1936], Ammianus Marcellinus. With An English Translation, vol.2, 1936

- Rolfe, John C. [1939], Ammianus Marcellinus. With An English Translation, vol.3, 1939

- Ross, Alan J. [2016], Ammianus' Julian: Narrative and Genre in the Res Gestae, 2016

- Seyfarth, Wolfgang [1978a], Ammiani Marcellini Rerum gestarum libri qui supersunt, vol. 1, 1978

- Seyfarth, Wolfgang [1978b], Ammiani Marcellini Rerum gestarum libri qui supersunt, vol. 2, 1978

- Tomlison, George [1843], On the Flaminian obelisk, in Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature of the United Kingdom, 2nd series - vol. 1, 1843, pp. 176 - 191

- Westerfeld, Jennifer Taylor [2019], Egyptian Hieroglyphs in the Late Antique Imagination, 2019

Comments

Post a Comment