New England at the Black Sea... an 11th c. CE colony of English exiles after the Norman Conquest of Britain in 1066 CE, as narrated in the Chronicon Laudunensis

The narrative is included in a chronicle, compiled by a monk in Laon of northern France during the 13th c. CE [after 1219 CE], known under the title 'Chronicon Universale Anonymi Laudunensis'. And it's preserved in two latin manuscripts; B : Berlin Ms. Phill. 1880, f. 111v-114r [in staatsbibliothek-berlin], & P : Paris BNF Latin 5011, f. 117v-120v [in gallica]. The latter being early copy of the former [Ciggaar [1974], p. 301-302, Rodgers [1981], p. 86].

The text seems to be the base for a part of the Icelandic saga of Edward the Confessor ['Saga Játvarðar konungs hins helga']; or at least both texts, latin & icelandic, had used a common source. This Saga most possibly was compiled in the 14th c. CE [Fell [1972], p. 258, Rodgers [1981], p. 84].

- The transcription is taken from Ciggaar [1974], p. 320-323. Ciggaar has expanded the scribal abbreviations from the mss incorporating them in the text, on which I added some letters with brackets, so the text to be more comfortable [eg. the usual a before e -> (a)e]. While at really few instances there was a comparison with the manuscripts, where I give a relevant footnote.

- My translation is aiming history, so I tried to make it as faithful as possible but also readable.

Parts:

01 • 02 • 03 • 04 • 05 • 06 • ref

Part 01: Some English nobles submitted themselves to William the Conqueror, some didn't ▲ up

|

Willelmus rex Angli(a)e benignissimus cunctis principibus qui cladi

factatae1 de eorum gente superfuerunt mandavit ut nichil

metuentes hominium sibi et fidelitatem prestarent, ipse vero omnem

eorum ingenuitatem, libertatem et honorem fideliter conservaret. Ad

hanc regis pollicitationem multi nobilium Anglorum regi se submiserunt

quibus a rege reverenter susceptis et assecuratis pr(a)ecepit in pace

manere. In occiduis vero partibus quas Angli West appellant circa Sabrinum fuerunt quidam nobiles qui tanto sunt dolore tantaque m(a)estitia affecti super regno amisso et ingenuitate perdita quod in omnibus regem multa pollicentem obaudirent eligentes potius vel mori vel a patria perpetuo eliminari quam videre advenas su(a)e gentis dominari. Inter hos fuerunt principui2 Stanardus, Bricthniatus, Frebern. |

William king of England, the most kind, have recommended to all the

princes, the ones from their nation who have survived the done

disaster, to offer faith and homage to him fearing nothing; for he

truly will conserve faithfully every of their nobilities, liberties

and honors. At this king's promise many English nobles have

surrendered to the king; who, being acknowledged and reassured by the

king reverently, have been advised to stay in peace. But in the western regions, that English call 'West', some nobles have been around Sabrinus [river]. These have been affected by such anger and sorrow regarding the lost kingdom and wasted nobility, for they obeyed in all things the much promising king, choosing rather to die or to be banished permanently from their native land than to see the foreigners dominate their nation. Among them they have been the leaders Stanardus, Bricthniatus, Frebern. |

English - history notes:

- The characterization of William the Conqueror as most kind - beneficent ['benignissimus'] is according to Ciggaar [1974, p. 324] an indication that the text was written in a Norman environment. At the relevant point, the Icelandic Saga is mentioning him as 'William the bastard', Dasent [1894, p. 425].

- Sabrinus - Sabrina: the river Severn in Wales.

- The 'much promising king' should be Harold Godwinson here, being in contrast with king William the Conqueror.

Latin - grammatical notes:

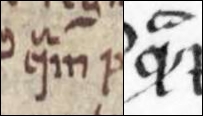

- factatae: dat.sing.fem. of perf.pass.part. of facto [= done, already occurred]. Here Ciggaar seems not sure, giving 'facere' with a question mark. I could read: in B [with some difficulty] ' fact̅te ' -> ' fact(a)t(a)e '; in P ' fc̄e ' -> ' f(a)c(ta)e ' or ' f(a)c(tata)e ' [fig.01]. In any case suitable

- principui -> principes [probably here]

|

| fig.01: for gram.fn.01 |

Part 02: The still resisting English are sending an embassy to Denmark asking for help... and William's reaction ▲ up

|

Hii tres fuerunt heroes quos Anglici corrupto idiomate herles vocant,

hos latine consules vel comites appellamus. Primus fuit comes

Cladicestrie, alter de Lichesfeld, tertius de Warevuic fuit. Fuerunt

et ali(a)e dignitatis3 viri qui a suis drenc(h)

nominabantur, qu(a)e dignitas prima fuit post heroes, hos possumus non

indigne barones vocitare. Horum primus fuit He(e)illoch, hic fuit

venator regum, Coleman, hic vir sanctus Constantinopoli habet templum,

Wicredus, Lee(t)chetel, Seman, Segrim, Alfem, Dunnigt, Wlston,

Vl(f)chetel, Aleuui, Leuuine. Hii omnes pari voto et studio

Normannorum dominium abominantes, tam hii quod omnes eorum subditi et

amici eorum neci incumbebant et terras eis subditas c(a)edibus,

rapinis et flammis iugiter destruebant. Tandem cognoscentes se regem

non posse sustinere miserunt de suis ad regem Dacorum4 ut

eis subvectaret5 auxilium opportunum, fuerunt qui hac

legatione functi sunt Godwinus iunior, frater Harardi nuper a

Normannis occisi et Haveloch de regia stirpe Dacorum ortus. Rex vero

Dacorum audita morte Harardi condoluit, auxilium eis pollicetur

festinum. Willelmus autem rex ad impediendum regis Dacorum propositum, Helsinum abbatem Rameseie virum religiosum et eloquentem cum regali munificentia misit et impetrata pace regi Willelmo... AD MLXXII |

These three [Stanardus, Bricthniatus, Frebern] have been heroes, whom

Englishmen call by a corrupted idiom 'earls', and in latin we call

them consuls or counts. The first have been count Cladicestrie, the

other of Lichesfeld, the third of Warevuic. They have also existed men

of another dignity, that has been the first dignity after heroes.

These were called by their own [people] 'drench', we can call them not

unworthily barons. From these first have been He(e)illoch, this [man]

have been kings' minister [chief-hunter], Coleman, this holy man has a

temple in Constantinople, Wicredus, Lee(t)chetel, Seman, Segrim,

Alfem, Dunnigt, Wlston, Vl(f)chetel, Aleuui, Leuuine. All these were

abominating the Norman rule with equal will and zeal, so much that all

their subjects and friends inclined to murder and destroyed

perpetually their subject-lands with assassinations, plunderings and

fires. Finally knowing that king can't keep standing, have sent

[ambassadors] about their [affairs] to the king of the Danes so that

he would bring suitable help to them; and these who have been in

charge of this embasssy, have been Godwinus the younger, brother of

Harard who was recently killed by the Normans, and Haveloch, coming

from the royal lineage of the Danes. The king of the Danes indeed,

when the death of Harard was learnt, has suffered greatly and he

promises them quick help. But king William, so to hinder the plan of the Dane king, has sent Helsinus abbot of Ramsey, religious man and eloquent, with royal gifts and procured peace [treaty] with king William... AD 1072 |

English - history notes:

- The name of the Dane king isn't given here; in the Icelandic Saga is written Sweyn, who is Sweyn II of Denmark [c. 1019 - 1076].

- Harardus - Haraldus is mentioned as recently killed by the Normans; it should be implied Harold Godwinson.

- Regarding the English princes, the Icelandic Saga mentions by name only Sigurd, earl of Gloucester, who should correspond to Stanardus count Cladicestrie here; and actually not on this embassy to Denmark but on their following departure: "There were three earls and eight barons who were their leaders, and the foremost of them was Sigurd earl of Gloucester", transl. Dasent [1894], p. 425, cf. Fell [1974], p. 182.

- Ciggaar [1974, p. 329] mentions some difficulty identifying this Godwin as brother of Harold, whom the English sent. While there's a discrepancy-contradiction with the Saga that mentions some Godwinus as envoy of William. Specifically: "But when William heard of those messages, then he sent south (?) to Denmark Godwin the young, Godwin's son, and along with him a famous bishop," with the manuscript note: "the son of earl Baldwin", in Dasent [1894], p. 425..

- Ciggaar [1974, p. 329] is noting references of this embassy to Danes in excerpts from (a) the church history of Orderic Vitalis of the 12th c. [pars II, lib. IV, ch. III, in PL 188, 308], and previously from (b) the Gesta Willelmi by William of Poitiers of late 11th c.

- The result of this counter-embassy of William with Helsin the abbot, isn't totally clear in this narrative, but can be deduced. In the Saga, William's success and English failure are more obvious.

- Ciggaar included few lines ahead from the mss, that I omitted here. They are only about the return-journey of Helsin the abbot from Denmark, a dangerous sea-storm that he faced and an angel's rescue - miracle. This religious narrative seems appearing in the writings of Anselm of Canterbury of the early 12th c. [PL 159, 325-326: Miraculum de Conceptione Sanctae Mariae]. Also in a french poem by Robert Wace of the later 12th c. [La conception Nostre Dame: Blacker, Burgess, Ogden [2013], p. 58ff]. In both this was about this counter-embassy; in both this Helsin's mission in Denmark was successful.

Latin - grammatical notes:

- dignitas: worth, merit, but also dignity, office

- Dacorum: gen.pl. of Dacus = medieval name for Dane here; it could also mean Dacian

- subvectaret: 3rd.sing.imp.activ.subj. of subvecto = subveho

|

| a map-route, based on the Angelino Dulcert's Europe map of 1339 [BNF GE B-696] with the red arrow-route drawn by me |

Part 03: The journey to the Mediterranean sea ▲ up

| Principes Angli(a)e qui regi Willelmo subesse noluerunt apparatis navibus et cunctis qu(a)e itineri eorum necessaria fore credebant Domino se committentes cum ducentis et triginta quinque navibus maria sulcant. Et venientes apud Septam munitam urbem paganorum cunctis civibus ab eis peremptis magnam auri et argenti copiam et nobilium indumentorum lucrati sunt, ita quod nullus in omni eorum multitudine pauper vel egens inveniebatur per habundantia6 sericorum pannorum nec poterat quidquid in Anglia possederant huic eorum felicitati vel prosperitati comparari7. Tandem insecuntur8 eos pagani cum exercitu magno in quos ita debac(c)hati sunt Christiani ut xxxii milia eorum gladio perimerent, multis eorum in mari submersis. Pagani vero his rumoribus perterriti urbes qu(a)e in eorum erant itinere vacuas relinquerunt9 ad Africam transfretantes. | The English princes, who don't want to submit to king William, with the ships ready and all these that they thought will be necessary for their journey, entrusting themselves to Lord, they sail over the seas with 235 ships. And approaching near fortified Septa, pagan city, after all citizens were killed by them, they have gained a great quantity of gold and silver and of noble garments. In such way that noone within all their multitude was found poor or needy cause of the abundance of silk cloths; nor could be compared whatever they had in England to this happiness or prosperity of theirs. Finally pagans follow them with a great force, against whom in such way the christians have raged, so that they killed 32 thousands of these with the sword, while many of these were drawn in the sea. Pagans, truly terrified by these rumors, have left behind the cities empty, that were in their way, passing to Africa. |

|

Baleares quoque insulas qu(a)e sunt ad prospectum Ispanie quas

indigen(a)e10 nunc Maoricas et Minoricas appellant omni

evacuatas habitatore relinquerunt rege eorum perempto quaeque11

pretiosa sibi tollentes. Deinde venientes ad Sardiniam primo quidem

ceperunt pr(a)ed(a)e et incendiis vacare, sed cum cognovissent Sardos

Christianos esse cuncta ablata eis restituerunt et super aliis dampnis

eis humiliter satisfecerunt, quibus principes Sardini(a)e pro eorum

modestia servos mille trescentos gratis dederunt, quibus naves quas

adquisierant12 interfectis Sarracenis munierunt. Exinde

audierunt Constantinopolim a paganis fuisse obsessam illuc properant

quam citius et irruentes inopinate in eos cunctos quos in navali

hostico invenerunt aut ferro interfecerunt aut undis submerserunt. Die

vero sequenti navibus relictis terrestri proelio paganos invadere

ordinaverunt, sed venientes ad eorum tentoria neminem invenerunt.

Audita enim strage suorum aufugerant metu peregrinorum. Acta sunt hec Anno Domini MLXXV. |

Likewise they [=English] have left empty from every inhabitant the

Balearic islands, taking anything precious to them, after their king

was killed; [these islands] are on the view of Spain and the natives

now call them Majorcas and Minorcas. Then reaching at Sardinia,

firstly they have chosen indeed to spend time on booty and fires. But

when they had learnt that Sardinians were christians, have returned

all the stolen to them and regarding the rest damages they have

satisfied them humbly; to whom the princes of Sardinia have given

freely for their modesty 1300 slaves and to whom have provided ships,

that had acquired from the killed Saracens. Then they have heard that

Constantinople have been besieged by the pagans; to there they have

rushed how quickly and charging unexpectedly against all these whom

have found in the enemy fleet, either they have killed them with the

sword or they have sunk by the waves. On the following day with the

ships abandoned, they have arranged to move against the pagans in a

ground combat, but approaching towards their tents they have found

nobody. For when the defeat of their people was heard, they had fled

by the fear of the strangers. These are the facts, AD 1075 |

English - history notes:

- Regarding the narrated siege of the Constantinople, Ciggaar [1974, p. 306ff] is considering between two events; the one of 1074-5, the other of 1091. The former during the reign of Michael VII Doukas, Parapinakes, the latter of Alexios I Komnenos. But both with the Pechenegs as involved opponents. Ciggaar seems prefering the former, despite the mention of Alexios. This event of 1075 should be narrated by Attaleiates [1852, p. 208-209] and Zonaras [Ep. 17.17, PG 135, 281] | see also Paroń [2021], p. 353, cf. Vasiliev [1952], p. 355-359.

- In our latin narrative the naval route is mentioning firstly Septa [probably the city near Gibraltar], then the Balearic islands [Majorca and Minorca], Sardinia, Constantinople. The Icelandic Saga is more detailed regarding some places. They are mentioned in order: Mathewsness, Galicia -land, Norva - sound, Septa, Majorca and Minorca, Sicily, Constantinople. Difference: Sicily instead of Sardinia.

- The Icelandic Saga mentions 350 ships instead.

- In the Saga Constantinople is written as Micklegarth, while emperor Alexios as Kirjalax.

Latin - grammatical notes:

- habundantia -> abundantia = abundance

- comparari: pres.pass.inf. of comparo = compare. Here Ciggaar is giving comperari instead; I couldn't find some alternate spelling like this, without meaning that there's not. I can read in both B & P ' cōքari ' that could be both co(m)p(ar)ari or co(m)p(er)ari [fig.02].

- insecuntur -> insequuntur = 3rd.plur.pres.act.ind. of insequor

- relinquerunt -> reliquerunt = 3rd.plur.perf.act.ind. of relinquo

- indigen(a)e: equivalent to indigeni = native, indigenous

- quaeque. Here Ciggaar is giving quidque instead; not actually with a different meaning. quaeque seemed more suitable cause of the following pretiosa, while the mss help. I can read in B ' q̄q; ' & in P ' q̄; ', both suitable [fig.03].

- adquisierant -> acquisiverant (?) = 3rd.plur.pluperf.act.ind. of acquiro = acquire

|

| fig.02: for gram.fn.07 |

|

| fig.03: for gram.fn.11 |

Part 04: The reception by Alexios I Komnenos & the Varangian guard ▲ up

|

Alexis imperator Grecorum et universi principes cum ingenti favore

eos receperunt in urbem et cognito quod ullius mercedis spe sed solo

Christianitatis amore se discrimini obtulerant, honores divitias eis

largiti sunt affluenter. Imperator vero cum postea per eos cognovisset

causam peregrinationis eorum esse quod se noluerunt regi extraneo

subici dedit eis locum mansionis in urbe regia. Insuper municiones13

eorum primoribus largitus est agros et vineas. Redditus14

quam15 plurimos universis contradidit16.

Custodiam sui corporis et uxoris su(a)e et filiorum suorum et

univers(a)e regi(a)e stirpis eis credidit et eorum heredibus imperium

defendendum scripto sigillato confirmavit. Set cum imperator cum

Grecis dixisset h(a)ec debere exulibus sufficere17, cuncta

imperatoris dona et promissa nichili ducentes recedere maturaverunt. A

quibus tamen inpetravit imperator ut aliqui eorum in urbe regia

remanerent. Numerus remanentium iiii.ccc.l. |

Alexios emperor of the Greeks and all princes have accepted them in

the city with great favor. And they have granted honors & riches

to them copiously, being acknowledged that by the hope of some reward

but also by the sole love of christianity, they had exposed themselves

in danger. And the emperor, when afterwards had learnt by them that

the reason of their journey was because they didn't wish to submit

themselves to a foreign king, has offered to them a region of

residence in the royal city. Furthermore he has granted fortifications

to their leaders, lands and vineyards. He has distributed the very

most properties to all. He has entrusted the protection of his own and

his wife and his sons and the entire royal lineage to them and to

their heirs, the defense of the empire; he has confirmed it with

sealed document [sigillatum]. But when the emperor along with the

Greeks had said to the exiles that they own to provide these, they

have rushed to recede considering all the emperor's gifts and promises

of no value. Nevertheless the emperor has obtained from these that

some of them would stay in the royal city. The number of the remaining 4350 [?]. |

English - history notes:

- The latin text doesn't give the term Varangian; the Saga does.

- An excerpt mentioned by Ciggaar [1974, p. 329], though it could fit at many instances, it's also proper here. Orderic Vitalis of the 12th c. wrote about the English after the Norman conquest: 'But some of them [English] flourishing with the flower of the beautiful youth, have gone to distant regions, and have offered themselves audaciously to the army of emperor Alexios'. Continuing Orderic mentions the help they offered to Alexios against Robert Guiscard of Apulia and Normans, and that Alexios granted a city to them, Chevetot [Church history, pars II, lib. IV, ch. III | in PL 188, 308].

Latin - grammatical notes:

- municiones -> munitiones [more possibly] = defences, fortifications

- redditus: acc.pl. of redditus = revenue, income, property that produces income. Most probable, connected with reditus [DMLBS]

- quam: adv. with superlative adj. plurimos; seems fitting. Ciggaar is giving instead: quarum. I could read in mss: in B ' q̄m ' in P ' _q° ' [fig.04]. Both suitable

- contradidit: 3rd.sing.pres.act.ind. of contrado [or even contra-dido] = to deliver together or wholly [Lewis-Short].

- the syntax seems a little confusing. But it's clear that the English exiles [exulibus] ought to provide these [the aforementioned guarding duties], and after calculation they receded rejecting. Then 'exulibus' could be a dative personal/subject of an impersonal inf. 'dubere'; or could be ind.obj. in dative of 'dixisset' and afterwards implied as subject of debere and sufficere. More possible the former.

|

| fig.04: for gram.fn.15 |

Part 05: The Nova Anglia, at Domapia of the Black Sea ▲ up

| At eorum qui naves petierunt erat numerus infinitus. Tunc per brachium Sancti Georgii ad mare maius venientes ad Domapiam tendunt, ante annos xxxv. a paganis ab imperatore ereptam et inhabitatam. Omnibus itaque paganis ibi interfectis provinciam ceperunt incolere, cunctis imperii provinciis omni fertilitate pr(a)esta(n)tiorem et dampnato ab eis et deleto regionis illius nomine antiquo ad memoriam regionis de qua originem duxerant Angliam eam vocaverunt. Set et civitates nominibus civitatum Angli(a)e appellaverunt. Est autem regio pascuis uberrima, fontes salubres, flumina piscosa, saltus am(o)eni, agri fertiles, fructus gustu iocundi. Distat vero h(a)ec Nova Anglia ab urbe regia bis tridua navigatione versus septentrionem18, in initio Scitice regionis. | Yet the number of these, who have asked ships, was infinite. Then approaching at the greater sea through the branch of St. George, they are directed to Domapia; that 35 years before, have been set by the emperor free from pagans and inhabited. Thus as all the pagans have been killed there, they have chosen to inhabit the province, excelling from all the provinces of the empire regarding every abundance; and with the ancient name of that region condemned by them and extinguished, they have called it Anglia for the memory of the land, from which they had derived their origin. Yet they have called the cities with the names of the English cities. Moreover, there is land for pasture most fruitful, beneficial fountains, fishy rivers, delightful forests, fertile lands, fruit pleasant in taste. And this Nova Anglia is distant from the royal city twice a 3-day journey towards Ursa Major, at the beginning of the Scythian region. |

|

Hungari regem suum Salomonem regno deturbatum sub custodia excruciant

et imperatori rebellant. Gelum magnum fit a kal. nov. usque ad kal. maii cuius soliditas duravit usque ad medium aprilis. Nicephorus prothosimbolus19 Alexi imperatoris ab eo missus ad Anglos orientales ab eis tributa exigere ab eis occiditur. Unde imperator Grecorum consilio molitus est omnes Anglos occidere, cuius rei metu plurimi eorum ad Novos Anglos transierunt, plurimi piraticam exercuerunt. Set imperator p(a)enitens per apocrisiarios suos eos revocavit. Angli orientales nolentes Grecorum patriarche subesse miserunt clericos suos ad Hungariam in episcopos consecrandos, qui sunt sub iurisdic(t)ione Romani pontificis, qu(a)e res multum displicuit imperatori et Grecis. |

The Hungarians torture their king Solomon under custody, who has been

deprived of royal power, and they revolt against the emperor. The big cold is from the calends of November to the calends of May, whose solidity lasts till the middle of April. Nicephorus, leading advisor of the emperor Alexios, dies by the eastern English, to whom was sent by the emperor to require taxes from them. Therefore the emperor of the Greeks intentionally has attempted to kill all the English, of which many by fear of their affair have gone to the New English; the most have practised piracy. Yet the emperor displeased by his delegates has recalled them. The eastern Englishmen, not willing to submit to the patriarch of the Greeks, have sent their priests in Hungary to be consecrated bishops, who are under the jurisdiction of the Roman pontiff; a matter that has displeased very much the emperor and the Greeks. |

English - history notes:

- About the mentioned branch of St. George, seems that there could be two approaches: one could place it on the Danube delta at Romania, the other in the Marmara sea of Constantinople. Ciggaar [1974, p. 336] chooses the latter, and it seems more rational as it appears according to the latin text first before the greater sea, i.e. the Black sea; cf. Oration 'Quamvis omnibus' of Pope Pius II where: "Sunt enim angustiae per Bosphorum Thraciae ac per Hellespontum, quod Bracchium Sancti Georgii vulgus dictitat, in potestate Turcorum."

- In any case the destination [Domapia] is 6 days journey towards the north. The Saga repeats this distance but towards north-east, that could lead more easily near Crimea through the Black sea. While it's added that the capture of this new land was a suggestion of Alexios.

- The Saga is also giving two names of the new English colonies - cities, London and York.

- The English who stayed in the empire seem restless with some rebellious attitude; eg. regarding taxes and religion. They are called by the latin text as Angli Orientales, while Fell [1974, p. 188] concludes that "the term 'angli orientales' was the result of someone's distinction between English and Norwegian Varangians". The Saga doesn't mention the term, while in there the eastern church [after the schism of 1054] is mentioned as "St. Paul's law".

Latin - grammatical notes:

- septentrio: Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, north [DMLBS]

- prothosimbolus: from greek πρωτοσύμβουλος = leading/first counsel

Part 06: Hardigt the hero ▲ up

|

Henricus Romanorum imperator pervagatus Sueviam omnes municiones

hostium suorum subvertit quo facto hostibus formidinem amicis vero

fortitudinem auxit. Turci super Arabes et Sarracenos invaluerunt et

Armeniam et Siriam incursantes multas urbes et Antiochiam ceperunt. Angli orientales quendam Hardigt nomine miserunt ad imperatorem quem fama loquebatur fortissimum omnium Anglorum. Unde Grecis erat suspectus, qui callide leonem solverant qui eum devoraret. Remanserat enim solus in curia palatii. Ille vero ad columpnas marmoreas qu(a)e erect(a)e in atrio palatii erant cucurrit ut per eas a leone tutaretur et invento grandi palo quem ambabus manibus elevans columpnam habens a tergo20, secundo et tercio leonem percutiens, ad terram coegit iacere et currens per pedes posteriores eundem arripiens circuiundo21 cursitans caput leonis columpn(a)e elidens e(x)cerebravit22. |

Henry the emperor of the Romans, after spreading in Swabia, destroys

all the fortifications of his enemies, by which fact he has raised

fear to the enemies and truly strength to the friends. The Turks have

prevailed over the Arabs and the Saracens and attacking to Armenia and

Syria they have captured many cities and Antioch. Eastern English have sent a certain Hardigt by name to the emperor, and rumor had it that he was the strongest of all the English. Therefore he had been mistrusted by the Greeks, who had loosened a lion cunningly that would swallow him. For he had remained alone in the court of the palace. He indeed has run towards the marble columns, that are erected in the atrium of the palace, so to be protected from the lion by these; and when a big stake is found, which he raises with both hands being behind the column20, he has forced the lion to lie down on the ground, piercing it for second and third time; and as he's quickly seizing it by the hind feet while running all around so to surround it, he has brained the lion by striking its head to the column. |

| ... | ... |

| Hardigt de gente Anglorum quem supra leonem occidisse retulimus invidiose reus maiestatis accusatus contra duos Grecos fortissimos pedestri certamine suam indempnitatem23 defendit, nam alterum eorum brachio cum latere p(ra)erepto24 ad terram coegit et in alterum irruens caput usque ad pectus ei in duas partes dissecuit. Imperator vero eum principem omnium custodum suorum constituit et non multo post ducem navalis exercitus ordinavit. | Hardigt of the nation of the English, whom we have mentioned previously killing the lion, after being accused enviously as guilty for treason, he has defended his indemnity at a pedestrian combat against two Greeks most powerful. For he has confined the one of these on the ground, as the arm with the flank have been snatched; and rushing to the other he has cut his head all the way to the chest into two parts. The emperor indeed has appointed him chief of all his guards and not much later he has designated him as leader of the navy. |

English - history notes:

- A story that can't be found in the Icelandic Saga. These are two different excerpts, two incidents, with a distance of few paragraphs, but about the same person. The 1st is between the indicated years 1075 -1086 CE; the 2nd between the years 1086 -1090 CE.

- The mentioned capture of Antioch by the Turks and the relevant context [around the 1st incident], is written in a similar way by Sigebert of Gembloux [Chronicon] for the year 1079 CE, indicated by Cigaar.

- Different spellings of the English hero in the mss: Hardigt - Hardigch - Hardich.

- Ciggaar [1974, p. 338-339] makes an interesting comparison with Hardinus de Anglia; a name found as a military-naval commander in a crusader expedition around 1100s [Albert of Aix, Hist. 9.11]. Though different approaches have been written on this [cf. Edgington [2013], p. 215].

Latin - grammatical notes:

- columpnam habens a tergo: literally 'having column behind/at the back'-> understood as 'sticking his back at the column, so to use it as cover and to be protected', 'to be round the column', this interpretation after the rest context where he has ran to the columns for protection and stayed there to fight. Because just having a column generally somewhere behind him in this case, would seem irrelevant [even afterwards he surely doesn't go too far away from the column as he will crash the head of the lion on it]. I tried to give this scene shortly with 'being behind the column', using behind with a sense of protection. Other versions seemed extended.

- circuiundo -> circueundo: dat. gerund of circueo [=circumeo]. Here as dative of purpose.

- A difficult syntax cause of the many participles. Regarding the verb types my understanding indicates: (i) e(x)cerebravit: main verb [mv]; (ii) elidens: participle of manner/means dependant on mv; (iii) arripiens: participle of manner or contemporary time dependant on mv; (iv) currens: participle of manner dependant on 'arripiens', almost adverbial; (v) cursitans: participle of contemporary time [or maybe manner] dependant on 'arripiens'; (vi) circuiundo: gerund in dative of purpose dependant on 'cursitans'.

- indempnitatem: acc.sing. of indem(p)nitas = security from possible damage or loss, indemnity, payment, indemnification. Not totally sure if here 'defending his indemnity' would mean 'defending' some given guarantee.

- brachio cum latere p(ra)erepto. In Ciggaar is written 'eum' instead of 'cum', which creates difficulties. I think that it's just a typo, comparing it with the mss and other instances in Ciggaar's transcription. In both B + P, I could read ' cū ' [fig.05]. Ciggaar is also giving 'perepto'. I think that 'praerepto' [from 'praeripio'] is more suitable, without changing the meaning as both could include rapio. In both mss I could read ' p̄repto ' [fig.05]; suitable. The possibility of 'perempto' was also attractive [so to be translated as a 'destroyed arm'], but the mss didn't help. At two other instances, for the passive participle of perimo-> perempt-us, B was using the scribal abbreviation ' ꝧemt- ', and P the ' ꝧe̅pt- '. None was using the ' p̄rept- '

|

| fig.05: for gram.fn.23 |

References ▲ up

- Alvarez, Sandra [2014], English Refugees in the Byzantine Armed Forces: The Varangian Guard and Anglo-Saxon Ethnic Consciousness, web article in deremilitari.org/

- Attaleiates Michael, History, in Corpus scriptorum historiae Byzantinae, 1852

- Blacker, Jean, Burgess, Glyn S., Ogden, Amy [2013], Wace, The Hagiographical Works: The Conception Nostre Dame and the Lives of St Margaret and St Nicholas, 2013

- Ciggaar, Krijnie N. [1974], L'émigration anglaise à Byzance après 1066. Un nouveau texte en latin sur les Varangues à Constantinople, in Revue des études byzantines, vol 32, 1974, pp. 301-342

- Dasent [1894], Saga of Edward the Confessor (Dasent, G. W., ed. & transl), in the Icelandic Sagas, vol. 3, 1894, pp. 416-428

- Edgington, S. (ed. - transl.) [2013], Albert of Aachen's History of the Journey to Jerusalem, Vol. 2, 2013

- Fell, Christine [1972], The Icelandic saga of Edward the Confessor: the hagiographic sources, in Anglo-Saxon England, Vol. 1 (1972), pp. 247-258

- Fell, Christine [1974], The Icelandic saga of Edward the Confessor : its version of the Anglo-Saxon emigration to Byzantium, in Anglo-Saxon England vol. 3 (1974), pp. 179-196

- Rodgers, Leslie [1981], Anglo-Saxons and Icelanders at Byzantium, with special reference to the Icelandic Saga of St. Edward the Confessor, in Byzantine Papers 1981, pp. 82-89

- Vasiliev, Alexander A. [1952], History of the Byzantine Empire 324-1453, 1952

- Paroń, Aleksander [2021], The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe, 2021

- PG, Patrologia Graeca

- PL, Patrologia Latina

for the latin text analysis were mainly used:

- Charlton T. Lewis & Charles Short, A New Latin Dictionary, 1891

- Niermeyer, J. F., Mediae Latinitatis Lexicon Minus, 1976

- Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources

- Du Cange's, Glossarium mediae et infimae latinitatis

- Dictionaries in https://logeion.uchicago.edu/

- Dictionaries in https://lsj.gr/

- Latin dictionary in https://en.wiktionary.org/

- Joseph Henry Allen, James Bradstreet Greenough, Allen and Greenough's New Latin Grammar for Schools and Colleges, 1903

- Cappelli, Adriano [1928], Lexicon abbreviaturarum, 1928

- Deciphering scribal abbreviations, web article in the Library Of Congress, in loc.gov

Comments

Post a Comment